Shangri-La Socialism

Much myth surrounds Shangri-La, a hidden paradise in mountainous Tibet. The Theosophists believed Tibet to be the abode of the Mahatmas (Great Souls), keepers of the wisdom of Atlantis who congregated in a secret region of Tibet to escape the increasing levels of magnetism produced by civilization; they believed as well that the Tibetans were unaware of the Mahatmas' presence in their land.

In James Hilton's 1933 novel Lost Horizon, what makes Shangri-La invaluable is not the indigenous knowledge of the indigenous people, but that over the centuries of his long life, a Belgian Catholic missionary had gathered all that was good in European culture. They lived in the lamasery of Shangri-La, which towered physically and symbolically above the Valley of the Blue Moon, where the happy Tibetans lived their simple lives. For centuries many of Tibet's devotees have most valued not the people who live there but the treasures it preserves.

China had been a particular favorite of the French Enlightenment, which saw the rule of a huge population by a class of scholar-gentlemen, the mandarins, as an ideal. This was an early manifestation of the continuing European romance in which the West perceives some lack within itself and fantasizes that the answer, through a process of projection, is to be found somewhere in the East.

The Theosophical Society was founded in New York in 1875 by Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky and Colonel Henry Steele Olcott. Its goals included the formation of a universal brotherhood regardless of race, creed, sex, caste, or color; the encouragement of studies in comparative religion, philosophy, and science; and the investigation of unexplained laws of nature and the powers latent in man. It was in many ways a response to Darwin, yet rather than seeking in religion a refuge from science, it attempted to found a scientific religion, one that accepted the new discoveries in geology and embraced an ancient and esoteric system of spiritual evolution more sophisticated than Darwin's.

Madame Blavatsky herself claimed to have spent seven years in Tibet as an initiate of a secret order of enlightened masters called the Great White Brotherhood. These masters, whom she called Great Teachers of the White Lodge or Mahatmas (great souls), lived in Tibet but were not themselves Tibetans.

But many myths were of Tibetan making. Long before the Theosophists wrote of the secret region where the Mahatmas reigned, before James Hilton described the Edenic Valley of the Blue Moon in Lost Horizon, Tibetans wrote guidebooks to idyllic hidden valleys.

During the nineteenth century Tibet and China were regarded by many European scholars and colonial officers as "Oriental despotisms," one ruled by a Dalai Lama, an ethereal "god-king," the other by an effete emperor. As early as 1822, Hegel, discussing Lamaism in his Lectures on the Philosophy of History, found it both paradoxical and revolting that the Dalai Lama, a living human being, was worshipped as God. After the success of the Communists in China in 1949, the image of the Oriental despot resurfaced and was superimposed onto Chairman Mao, not as emperor but as the totalitarian leader of faceless Communists. The Chinese invasion and occupation of Tibet was perceived not as a conquest of one despotic state by another, but as yet another case of opposites, the powers of darkness against the powers of light. The invasion of Tibet by the People's Liberation Army in 1950 was (and often is still) represented as an undifferentiated mass of godless Communists over running a peaceful land devoted only to ethereal pursuits, victimizing not only millions of Tibetans but the sometimes more lamented Buddhist dharma as well. Tibet embodies the spiritual and the ancient, China the material and the modern. According to this logic of opposites China must be debased for Tibet to be exalted; for there to be an enlightened Orient there must be a benighted Orient; the angelic requires the demonic.

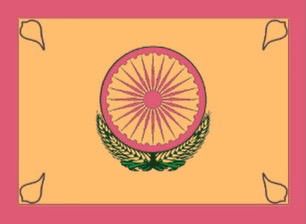

Thus Maoist Authoritarian Communism must be contrasted with Tibetan Buddhist Socialism as a political ideology which advocates socialism based on the principles of Buddhism. Both Buddhism and socialism seek to provide an end to suffering by analyzing its conditions and removing its main causes through praxis. Both also seek to provide a transformation of personal consciousness (respectively, spiritual and political) to bring an end to human alienation and selfishness.

Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama of Tibet has said that:

“Of all the modern economic theories, the economic system of Marxism is founded on moral principles, while capitalism is concerned only with gain and profitability. (...) The failure of the regime in the former Soviet Union was, for me, not the failure of Marxism but the failure of totalitarianism. For this reason I still think of myself as half-Marxist, half-Buddhist.”

The Chinese government claims it will control how the 15th Dalai Lama will be chosen, contrary to centuries of tradition. Chinese government officials repeatedly warn "that he must reincarnate, and on their terms."

When the Dalai Lama confirmed a Tibetan boy in 1995 as the reincarnation of the Panchen Lama, the second-ranking leader of the Gelugpa sect, the Chinese government took away the boy and his parents and installed its own child lama. The Dalai Lama's choice, Gedhun Choekyi Nyima's whereabouts are still unknown. The government's selection appears at official events to praise Communist policy and is viewed as a fraud by Tibetans.

Tibetan Buddhist Socialism is an alternative path to Maoist Authoritarian Communism. It is through the inspiration of the myth of Shangri-La that we are invited to participate in an enlightened sense of socialism.

Comments

Post a Comment