Religious Pluralism and Christian Anarchism

William James’s most direct and significant contributions to philosophy of religion come from his “The Will to Believe” and The Varieties of Religious Experience – the second of which having the greater influence on the development of religious pluralism during the twentieth century. The few speculations James offers about the nature of ultimate reality toward which religious experiences point suggest a relatively pluralist attitude toward the diversity of religions, according to which none could claim a monopoly on genuine experience of the divine nor be excluded from it. Together with his later writings on pragmatism and pluralistic metaphysics, James serves as important touchstone for later theories of religious pluralism. This religious pluralism is a form of religious anarchism.

Christianity began primarily as a pacifist and anarchist movement. Jesus introduces anarchism to the kingdom of God. Jesus is said, in this view, to have come to empower individuals and free people from an oppressive religious standard in the Mosaic law; he taught that the only rightful authority was God, not Man, evolving the law into the Golden Rule. This is the Truth that all religions point to.

German philosophers of religion Ludwig Feuerbach and Ernst Troeltsch concluded that Asian religious traditions, in particular Hinduism and Buddhism, were the earliest proponents of religious pluralism and granting of freedom to the individuals to choose their own faith and develop a personal religious construct within it; Jainism, another ancient Indian religion, as well as Daoism have also always been inclusively flexible and have long favored religious pluralism for those who disagree with their religious viewpoints. The Age of Enlightenment in Europe triggered a sweeping transformation about religion after the French Revolution, with rising acceptance of religious pluralism. These pluralist trends in the Western thought, particularly since the 18th century, brought mainstream Christianity and Judaism closer to the Asian traditions of religious and philosophical pluralism.

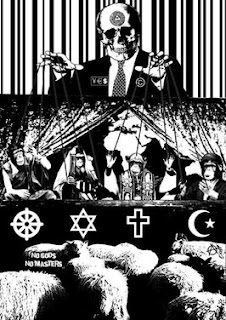

The anarchist critique has been extended toward the rejection of non-political centralization and authority. Bakunin extended his critique to include religion, arguing against both God and the State. Bakunin rejected God as the absolute master, saying famously, “if God really existed, it would be necessary to abolish him.” This atheism may flourish under religious anarchism, as the religious principle of love in action transcends theism and atheism.

There are, however, religious versions of anarchism, which critique political authority from a standpoint that takes religion seriously. Anarchism can be found in Taoism. There are also identified anarchist threads in Islamic Sufism, in Hindu bhakti movements, in Sikhism’s anti-caste efforts, and in Buddhism.

Many early Taoists such as the influential Laozi and Zhuangzi were critical of authority and advised rulers that the less controlling they were, the more stable and effective their rule would be. It is known, however, that some less influential Taoists such as Pao Ching-yen explicitly advocated anarchy. Anarchists such as Liu Shifu and Ursula K. le Guin have also identified as Taoists.

The Orthodox Kabbalist rabbi Yehuda Ashlag believed in a religious version of anarcho-communism, based on principles of Kabbalah, which he called altruist communism. Ashlag supported the Kibbutz movement and preached to establish a network of self-ruled internationalist communes.

The Indian revolutionary and self-declared atheist Har Dayal, much influenced by Bakunin, who sought to expel British rule from the subcontinent, was a striking instance of someone who in the early 20th century tried to synthesize anarchist and Buddhist ideas. Having moved to the United States, in 1912 he went so far as to establish in Oakland the Bakunin Institute of California, which he described as "the first monastery of anarchism.”

Christian anarchist theology views the kingdom of God as lying beyond any human principle of structure or order. Christian anarchists offer an anti-clerical critique of ecclesiastical and political power. Tolstoy provides an influential example. Tolstoy claims that Christians have a duty not to obey political power and to refuse to swear allegiance to political authority. Tolstoy was also a pacifist. Christian anarcho-pacifism views the state as immoral because of its connection with coercive violence.

Christian anarchism is a movement in political theology that claims anarchism is inherent in Christianity and the Gospels. It is grounded in the belief that there is only one source of authority to which Christians are ultimately answerable—the authority of God as embodied in the teachings of Jesus. It therefore rejects the idea that human governments have ultimate authority over human societies. Christian anarchists denounce the state, believing it is violent, deceitful and, when glorified, idolatrous.

More than any other Bible source, the Sermon on the Mount is used as the basis for Christian anarchism. The Sermon perfectly illustrates Jesus's central teaching of love and forgiveness. Christian anarchists claim that the state, founded on violence, contravenes the Sermon and Jesus' call to love our enemies. Christian eschatology and various Christian anarchists, such as Jacques Ellul, have identified the state and political power as the Beast in the Book of Revelation. Also some early Christian communities appear to have practised anarchist communism, such as the Jerusalem group described in Acts, who shared their money and labour equally and fairly among the members. Thomas Merton in his introduction to a translation of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers describes the early monastics as "Truly in certain sense 'anarchists,' and it will do no harm to think of them as such."

Religious pluralism with its many perspectives of the metaphysical realities is ultimately religious anarchism. No one perspective is to be elevated above the rest. This religious anarchism is a synthesis of radical theism and radical atheism, as no religion is the ultimate, other than the principle of love in action. It is this love in action that will build a world for a New Humanity.

Comments

Post a Comment